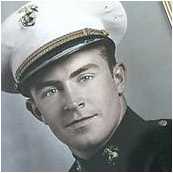

Norman F. Whittredge

Norman Whittredge’s sister Mary was 8 years old when the Marine officer came to her home in the South Boston projects to report his death. Mary, not her mom, answered that door. So much changed that day that it is Norman’s death, more than any event from the 5 years they shared together before he went to war at 17, that Mary remembers most about Norman.

That was the day the waiting began for Mary, her other brother, Norman’s fiancée and Norman’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Forrest Whittredge of O’Callaghan Way. Mary remembers it as the day her mom started the crying that came on so often for the balance of her life. She remembers it as tough growing up with that.

A year after he went missing Norman was declared dead, per public law 490, his name was placed on a memorial in the projects where he lived and his death benefits were paid. The family was given his medals- a purple heart, an Air Medal and a Distinguished Flying Cross. And, his death having been declared, Mrs. Whittredge was given his personal effects, among them his pilot’s wings, and a flag, “on behalf of a grateful nation”.

Mrs. Whittredge wore her son’s pilot’s wings for the balance of her life, and asked to wear them in her casket when she died thirty year later. To the best of Mary’s knowledge, Norman's mother never heard any further from the Military.

By the time Mary next heard of progress on her brother’s case Mary was a mother of 6 and a grandmother of 10. Norman’s memorial in the projects was long since removed. 58 years had passed with no news when an American with a passion for returning MIA’s, Bryan Moon went to Anami Oshima, Japan in 2003 in search of a different pilot. While he failed to find that pilot, Japanese press coverage of his efforts led to a call form the elderly Mrs. Shimao of Anami Oshima whose story, with time, may lead to Norman’s return home.

Mrs.’ Shimao’s husband Toshio Shimao was 27 years old in 1945 and based on the nearby island of Kakeroma. Having left University in Kyushu the year before, he was by then an officer in the Japanese Navy. He led a Kamikaze Squadron awaiting orders to man human piloted torpedoes, each 54 feet long and carrying 3000 pounds of explosives. It was to Toshio Shimao that Norman Whittredge’s dead body, along with his parachute, was brought once he landed. It was a stroke of luck for the Whittredge family.

Toshio Shimao was a humanitarian. After the war he was to become a renowned author in Japan, many of his works drawing form his experiences as a Kamikaze on Anami Oshima. But on that March day in 195 he was just a young officer facing a dilemma- what to do with the body. It had been a brutal war, and respect for the enemy dead was rare. Nonetheless, Mr. Shimao chose to bury it, with honors, in the village cemetery. As in all armies he had the body searched for intelligence. An unfinished letter to his sister Mary was found along with the usual personal effects. Mr. Shimao returned the letter to the body, and had it buried under a cross. Passions what they were, the cross was repeatedly removed by villagers, and repeatedly replaced by Shimao.

Five months later the war ended. Shimao never received his order to commit suicide on one of the torpedoes. But, sometime in the years after the war, Shimao told his wife of the man under the Cross, whose name he half remembered, and of the letter to Mary in his pocket. Although he died in 1986 Shimao’s act of decency survived him. All it took for Norman to be identified was for an American to be available to get the information. That’s where Moon came in.

To verify this extraordinary report of a Japanese officer's treatment of a fallen American airman, Moon’s team traveled to the southern end of Anami Oshima where they chartered a boat to reach the more remote island of Kakeroma and the cemetery which now rests unattended in a near deserted village.

An elderly lady who has lived in the village since pre WWII was the first to confirm the story of an American being buried in the cemetery. An interpreter then translated a second villager’s confirmation of these circumstances. The elderly lady guided the researchers to the cemetery and pointed to the now overgrown grave of the US MIA airman. The next day, after assimilating the news of this burial of an American MIA which has been a local secret for nearly 60 years, the Moon's, with their interpreter, visited the widow, Mrs. Shimao. To honor the deceased American airman, the elderly lady conducted a simple Japanese ceremony placing soil from the grave on a makeshift "boat", covered with flowers and with four incense sticks. She walked to the shore and cast the memorial on the water, kneeling at the waters edge as the memorial drifted gently out toward the sea.

Mary first heard of Norman’s presumed grave being found, and of Mrs. Shimao’s role in making it happen, in 2003. The two exchanged letters, and Mary and Mrs. Shimao planned to meet. Sadly Mrs. Shimao died before Mary could meet her.

After a few years waiting for progress on Norman’s return Mary asked her representatives for assistance in getting him back, but got no reply. Her friend, a West Point Graduate, then took on the case and was able to get her a casualty officer to represent Norman to the Marines.

While Norman’s remains may have been found, that have not yet been recovered. She still hopes he may be recovered before she dies. He was scheduled for recovery in 2007, but budget adjustments forbid it. Mary hopes that as the last surviving member of her family who knew Norman he’ll be returned before her death, and that she can introduce her children and grandchildren the brother she barely knew. She thinks it’s only right.

Thank you: Mary Hagan and Bryan Moon